Caregiver Corner: Facts on Caregivers

Caregiver Corner was created to provide facts and research about the Caregiver community that are often overlooked and underpaid because they are providing a service to their family member. The number of unpaid family caregivers in the U.S. increased by 9.5 million in the last 6 years and the number is increasing. This a testament that providing resources and financial assistance to Caregivers is an important part of the livelihood of all families. As the number of Caregivers continue to grow, Sam’s Caregiver Alliance Group hopes to bring awareness to the many foundations, organizations and the Tennessee Community about the importance of investing in services, resources and help to prevent Caregiver “burnout.”

MARKET SIZE AND TRENDS

A caregiver-sometimes called an informal caregiver-is an unpaid individual (for example, a spouse, partner, family member, friend, or neighbor) involved in assisting others with activities of daily living and/or medical tasks. In 2020, 41.8 million Americans provided unpaid care to an adult over the age of 50. That’s nearly 17% of the U.S. adult population. People with Alzheimer’s or Dementia are one of the leading reasons for needing caregivers. Over 11 million Americans provide unpaid care for people with Alzheimer’s or Dementia. In 2022, unpaid caregivers provided an estimated 18 billion hours of care valued at $339.5 billion. In 2023, Alzheimer’s or Dementia will cost the nation $345 billion. The total lifetime cost of care for someone with dementia was estimated at $392,874 in 2022 dollars. Seventy percent of the lifetime cost of care is borne by family caregivers in the forms of unpaid caregiving and out-of-pocket expenses for items ranging from medications to food for the person with the illness.

Alzheimer’s Association: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

MORTALITY RATE OF CAREGIVERS

According to a recent Stanford Medicine study, some 40 percent of Alzheimer’s caregivers die before the patient. It isn’t disease or accident that takes these caregivers, but rather the sheer physical, spiritual and emotional toll of caring for someone struggling with the Alzheimer’s.

The National Library of Medicine did a study on the mortality of Caregivers. See below:

https://www.nnlm.gov/reading-club/topic/251

Context: There is strong consensus that caring for an elderly individual with disability is burdensome and stressful to many family members and contributes to psychiatric morbidity. Researchers have also suggested that the combination of loss, prolonged distress, the physical demands of caregiving, and biological vulnerabilities of older caregivers may compromise their physiological functioning and increase their risk for physical health problems, leading to increased mortality.

Objective: To examine the relationship between caregiving demands among older spousal caregivers and 4-year all-cause mortality, controlling for sociodemographic factors, prevalent clinical disease, and subclinical disease at baseline.

Design: Prospective population-based cohort study, from 1993 through 1998 with an average of 4.5 years of follow-up.

Setting: Four US communities.

Participants: A total of 392 caregivers and 427 noncaregivers aged 66 to 96 years who were living with their spouses.

Main outcome measure: Four-year mortality, based on level of caregiving: (1) spouse not disabled; (2) spouse disabled and not helping; (3) spouse disabled and helping with no strain reported; or(4) spouse disabled and helping with mental or emotional strain reported.

Results: After 4 years of follow-up, 103 participants (12.6%) died. After adjusting for sociodemographic factors, prevalent disease, and subclinical cardiovascular disease, participants who were providing care and experiencing caregiver strain had mortality risks that were 63% higher than noncaregiving controls (relative risk [RR], 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00-2.65). Participants who were providing care but not experiencing strain (RR, 1.08; 95 % CI, 0.61-1.90) and those with a disabled spouse who were not providing care (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.73-2.58) did not have elevated adjusted mortality rates relative to the noncaregiving controls.

Conclusions: Our study suggests that being a caregiver who is experiencing mental or emotional strain is an independent risk factor for mortality among elderly spousal caregivers. Caregivers who report strain associated with caregiving are more likely to die than noncaregiving controls.

Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures

https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

The Hardships of Alzheimer’s Disease

The Hardships of Alzheimer’s Disease

The long duration of illness before death contributes significantly to the public health impact of Alzheimer’s disease because much of the time is spent in a state of sever disability and dependence. Alzheimer’s is a very burdensome disease, not only to the individuals with the disease, but also to their families and informal caregivers, and that, in recent years, the burden of Alzheimer’s has increased more dramatically in the United States. According to the most recent Global Burden of Disease classification system, Alzheimer’s disease rose from the 12th most burdensome disease or injury in the United States in the 1990 to the sixth in 2016 in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). In 2016, Alzheimer’s disease was the fourth highest disease or injury in terms of number of years lost (YLLs) and the 19th in terms of number of years lived with disability (YLDs). As of 2020 there were projected 120,000 people in Tennessee with Alzheimer’s and in 2025 there will be an expected 140,000 people with Alzheimer’s of Dementia which is an increase of 16.7%. [Alzheimer’s Association 2023] Caregivers often suffer with Elevated levels of depression and anxiety, Higher use of psychoactive medications, Poor physical health, Compromised immune function and Increased risk of early death yet while taking on the responsibility of caring for their loved. It is important for Sam’s Caregiver Support Group to eliminate some of this burden and provide an acceptable quality of life for the caregiver by support group meetings, respite reimbursement and educational programs.

African Americans as Caregivers

African Americans as Caregivers

Only recently have population-based studies examined racial disparities in dementia caregiving. Compared with White caregivers, Black caregivers are more likely to provide more than 40 hours of care per week (54.3% versus 38.6%) and care for someone with dementia (31.7% versus 11.9%). Black dementia caregivers are also more likely to provide help with the ADLs than White dementia. Black male dementia caregivers are 3.3 times more likely to experience financial burdens when compared with Black female and White male and female dementia caregivers, whereas Black and White male dementia caregivers are 37%-71% less likely than White female dementia caregivers to indicate emotional burden. Black dementia caregivers were found to be 69% less likely than White caregivers to use respite services, although the need for dementia care relief is considerable among Black families. [Alzheimer’s Association Disease Facts and Figures 2023]. Due to the lack of publicized respite resources in the African American community, Sam’s Caregiver Alliance Group will provide knowledge about all the respite resources in the Tennessee area and will also raise funds to provide respite reimbursement to caregivers primarily in the African/American community however people of all ethnic backgrounds will be eligible for our reimbursement program.

Black/African-American caregivers’ needs include greater education about dementia treatment and treatment of other disabilities, diagnosis and care strategies; navigating what is often perceived as a “broken” health care system; improved access to affordable transportation and health care services; greater education about navigation of family conflict; increased availability of respite support better communication about dementia within the Black/African-American community and increased availability financial/legal planning. [Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figure 2023]

New AARP Report Finds Family Caregivers Provide $600 Billion in Unpaid Care Across the U.S.

https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/

‘Valuing the Invaluable’ documents the increasing economic, physical and emotional costs of caregiving.

Money can’t buy the kind of care that family caregivers devote to their loved ones, from driving to appointments to managing medical claims to providing hands-on assistance. But if it could, the amount is staggering, according to the latest report in AARP’s “Valuing the Invaluable” series.

Care provided by millions of unpaid family caregivers across the U.S. was valued at $600 billion in 2021, the new report estimates, a $130 billion increase in unpaid contributions from the 2019 report. The staggering figure is based on about 38 million caregivers providing an average of 18 hours of care per week for a total of 36 billion hours of care, at an average value of $16.59 per hour.

For perspective, that amount is considerably more than the $433 billion spent by families nationwide in 2021 for all out-of-pocket U.S. health care costs. Put another way, the sheer act of trying to save $600 billion by setting aside $100,000 per year would take a total of 6 million years.

Economic value of family caregiving by state, 2023

Time is money. No one knows this better than the nation’s 38 million family caregivers who devote 36 billion hours of free care to older parents, spouses, partners and friends with chronic, disabling and serious health conditions. Family caregivers are the backbone of the long-term care system in the U.S. But with over 60 percent of family caregivers working either full-time or part-time — and 30 percent living with a child or grandchild — they need and deserve more assistance from city, state and federal governments, says the report. For instance, states can expand caregiving tax credits and workplaces can adapt more family-friendly policies such as paid family leave.

Caregiver Health

By Family Caregiver Alliance in cooperation with California’s Caregiver Resource Center and reviewed by Moira Fordyce, MD, MB, ChB.

A Population at Risk

An estimated 44 million Americans age 18 and older provide unpaid assistance and support to older people and adults with disabilities who live in the community. The value of this unpaid labor force is estimated to be at least $306 billion annually, nearly double the combined costs of home health care ($43 billion) and nursing home care ($115 billion).

Evidence shows that most caregivers are ill-prepared for their role and provide care with little or no support, yet more than one-third of caregivers continue to provide intense care to others while suffering from poor health themselves. Studies have shown that an influential factor in a caregiver’s decision to place an impaired relative in a long-term care facility is the family caregiver’s own physical health.

A substantial body of research shows that family members who provide care to individuals with chronic or disabling conditions are themselves at risk. Emotional, mental, and physical health problems arise from complex caregiving situations and the strains of caring for frail or disabled relatives.

Today, medical advances, shorter hospital stays, limited discharge planning, and expansion of home care technology have placed increased costs as well as increased care responsibilities on families, who are being asked to shoulder greater care burdens for longer periods of time. To make matters worse, caregivers are more likely to lack health insurance coverage due to time out of the workforce. These burdens and health risks can hinder the caregivers’ ability to provide care, lead to higher health care costs and affect the quality of life of both the caregiver and care receivers.

Impact of Caregiving on Caregiver Physical Health

High rates of depressive symptoms and mental health problems among caregivers, compounded with the physical strain of caring for someone who cannot perform activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing, grooming and other personal care activities, put many caregivers at serious risk for poor physical health outcomes. Indeed, the impact of providing care can lead to increased health care needs for the caregiver.

Caregivers are in worse health.

- About one in ten (11%) caregivers report that caregiving has caused their physical health to get worse.

- Caregivers have lower levels of subjective well-being and physical health than noncaregivers. In 2005, three-fifths of caregivers reported fair or poor health status, one or more chronic conditions, or a disability, compared with one-third of noncaregivers. Caregivers also reported chronic conditions (including heart attack/heart disease, cancer, diabetes and arthritis) at nearly twice the rate of noncaregivers (45 vs. 24%).

- Caregivers suffer from increased rates of physical ailments (including acid reflux, headaches, and pain/aching), increased tendency to develop serious illness, and have high levels of obesity and bodily pain.

- Studies demonstrate that caregivers have diminished immune response, which leads to frequent infection and increased risk of cancers. For example, caregivers have a 23% higher level of stress hormones and a 15% lower level of antibody responses. Caregivers also suffer from slower wound healing.

- The physical stress of caregiving can affect the physical health of the caregiver, especially when providing care for someone who cannot transfer him/herself out of bed, walk or bathe without assistance. Ten percent of primary caregivers report that they are physically strained.

Caregivers have an increased risk of heart disease.

- Caregivers exhibit exaggerated cardiovascular responses to stressful conditions which put them at greater risk than noncaregivers for the development of cardiovascular syndromes such as high blood pressure or heart disease.

- Women providing care to an ill/disabled spouse are more likely to report a personal history of high blood pressure, diabetes and higher levels of cholesterol.

- Women who spend nine or more hours a week caring for an ill or disabled spouse increase their risk of heart disease two-fold.

Caregivers have lower levels of self-care.

- Caregivers are less likely to engage in preventive health behaviors.

- Spousal caregivers who provide 36 or more hours per week of care are slightly more likely to smoke and consume more saturated fat.

- Compared to noncaregivers, women caregivers are twice as likely not to fill a prescription because of the cost (26% vs. 13%).

- Nearly three quarters (72%) of caregivers reported that they had not gone to the doctor as often as they should, and more than half (55%) had missed doctors appointments.

- Caregivers’ self-care suffers because they lack the time and energy to prepare proper meals or to exercise. About six in ten caregivers in a national survey reported that their eating (63%) and exercising (58%) habits are worse than before.

- Caregivers in rural areas are at a greater disadvantage for having their own medical needs met due to difficulty getting to the hospital and doctor.

Caregivers pay the ultimate price for providing care—increased mortality.

- Elderly spousal caregivers (aged 66-96) who experience caregiving-related stress have a 63% higher mortality rate than noncaregivers of the same age.

- In 2006, hospitalization of an elderly spouse was found to be associated with an increased risk of caregiver death.

A Place for Mom Caregiver Statistics

Caregiver Statistics: A Data Portrait of Family

Written by Claire Samuels (Learn more about the author)

https://www.aplaceformom.com/caregiver-resources/articles/caregiver-statistics

Nearly 17% of the U.S. adult population provides unpaid care to an adult over the age of 50. More than 75% of these caregivers are women, and on average they spend almost an equivalent number of hours a week providing care as people traditionally spend at a full-time job. Many of these caregivers are also employed or raising children of their own. Take an in-depth look at caregiver demographics by race, age, education status, and more.

Key facts about family caregiver statistics: An introduction

According to our research team’s analysis of the latest available data:

- In 2020, 41.8 million Americans provided unpaid care to an adult over the age of 50. That’s nearly 17% of the U.S. adult population.

- 89% of caregivers provide care for a relative or other loved one, such as a spouse.

- 23.7 hours per week is the average amount of time caregivers spend providing unpaid care for loved ones they don’t live with; those who live with their care recipient spend 37.4 hours a week.

- More than 75% of all caregivers are female.

- The average caregiver is 50.1 years old.

- Caregivers provide an estimated $470 billion in free labor each year.

Unpaid caregiver statistics

Family caregivers work long hours and are often unpaid for their time spent supporting loved ones. Many of these caregivers also have full-time jobs and other responsibilities, like raising children, volunteering, and doing housework and chores.

Unpaid family caregiving is on the rise

The number of unpaid family caregivers in the U.S. increased by 9.5 million between 2015 and 2020, from 43.5 million to more than 53 million. These numbers reflect a consistent increase in caregivers over time.

It’s important to note that not all unpaid caregivers assist seniors. The data above applies to caregivers of all adults, including younger adults with physical or mental disabilities.

However, a majority of the caregivers represented do support seniors. More than 41.8 million of the represented group care for people over the age of 50.

Unpaid caregiving can be long term

The average length of time a caregiver provides unpaid care to a loved one is 4.5 years.

Seniors with acute conditions may only require temporary care. For example, someone may have fallen or had surgery and they only need short-term care until they’ve healed enough to support themselves independently.

On the other end of the spectrum are seniors with persistent disabilities — diabetes, a stroke, loss of vision — that leave them unable to care for themselves in the long term. 11% of care recipients require assistance for more than 10 years.

The number of people providing care for five years or longer has increased from 24% in 2015 to 28% in 2020. As life-extending technologies improve, this number will likely grow.

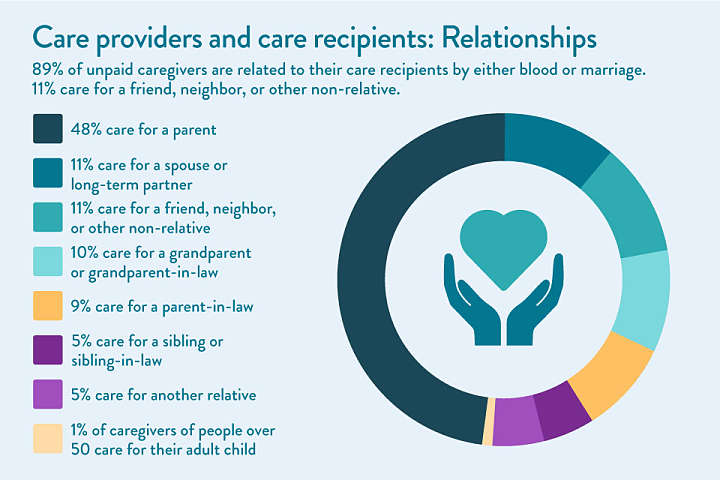

Care providers and care recipients: Relationships

Most unpaid caregivers are related to their care recipients. They often live near their loved ones, and they spend 20+ hours a week on active caregiving.

Relationships between caregivers and their loved ones

89% of unpaid caregivers are related to their care recipients by either blood or marriage. 11% care for a friend, neighbor, or another non-relative.

- 48% care for a parent.

- 11% care for a spouse or long-term partner.

- 10% care for a grandparent or grandparent-in-law.

- 9% care for a parent-in-law.

- 5% care for a sibling or sibling-in-law.

- 5% care for another relative.

- 1% of caregivers of people over 50 care for their adult child.

Between 2010 and 2020, the percentage of people caring for a spouse or partner remained steady. The number of people providing unpaid care to a non-relative dropped from 14% to 11%.

Time spent providing care

Family caregivers who live with their senior relative receiving care spend an average of 37.4 hours a week on direct caregiving duties. People who don’t live with their relatives spend an average of 23.7 hours a week on caregiving duties.

Note that these hours, which are almost equivalent to the number of hours worked in a standard full- or part-time job, don’t include passive time spent with care recipients. They encompass:

- Preparing meals for loved ones

- Cleaning and performing extra household duties

- Assisting with ADLs, like dressing or bathing

- Transportation to and from medical appointments

- Activities designed for the care recipient that the caregiver would not normally do, such as low-impact senior exercises in the home, reminiscence therapy, and craft projects

Caregiver demographics: Age, location, professional, and economic status

Caregivers in the U.S. aren’t a homogenous group. They differ in age, race, profession, and more.

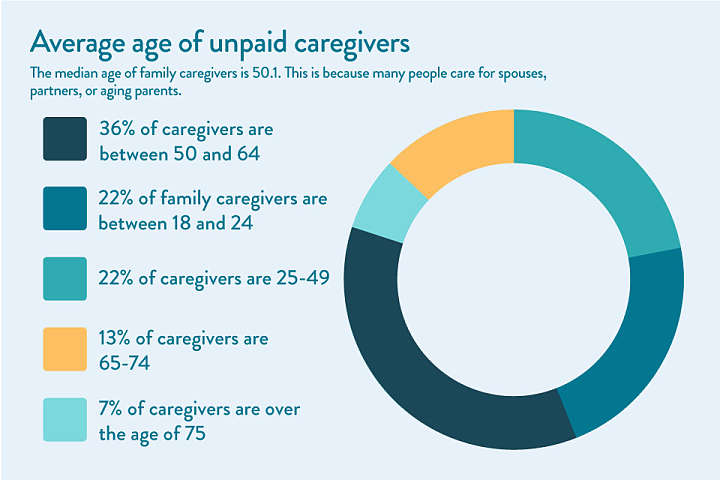

Average age of unpaid caregivers

The median age of family caregivers is 50.1. This is because many people care for spouses, partners, or aging parents.

- 22% of family caregivers are between 18 and 24.

- 22% of caregivers are 25-49.

- 36% of caregivers are between 50 and 64.

- 13% of caregivers are 65-74.

- 7% of caregivers are over the age of 75.

Marital status of family caregivers

The marital status of family caregivers of adults over 50 has changed significantly over the past 10 years. As of 2020, far more caregivers had never been married than in 2010. Here are the marital status percentages rounded to the nearest numbers:

- 60% of caregivers are married or in long-term domestic partnerships.

- 23% are single or never married.

- 9% are divorced.

- 3% are widowed.

- 2% are separated.

Family caregiver education status

The vast majority of unpaid caregivers finished high school, and most have completed at least some college. Here are the education statistics rounded to the nearest numbers:

- 6% of caregivers didn’t complete high school.

- 25% are high school graduates with no secondary education.

- 34% have attended either a technical school or some college.

- 21% are college graduates.

- Over 15% have completed graduate school or other tertiary education.

Family caregiver employment status

As of 2020, 62% of family caregivers were employed while caring for someone over age 50, while 38% were not employed. This striking statistic is partially due to caregiver age, as 20% of caregivers are over retirement age.

- Caregivers who are younger than 65 are more likely to work while caregiving (71%).

- Caregivers who provide care for 20 or fewer hours a week are more likely to be employed (66%).

- People providing care to a parent, grandparent, or in-law are more likely to work than those providing care to a spouse or partner.

- Men are more likely to work while providing care than women.

- 54% of caregivers are employed hourly, while around 40% are salaried, and others report being self-employed or owning their own business.

Rural caregivers

About 30% of caregivers live in rural areas. Rural caregivers are most often white women. They have, on average, lower incomes and education statuses than their urban and suburban counterparts. They also often care for younger loved ones: The average care recipient age in rural areas is only 66.9.

While most care recipients in the U.S. are female, rural care recipients are more likely to be male. Rural care recipients are more likely to have a greater number of health conditions than care recipients in urban and suburban areas, and they often require more assistance with medical and nursing tasks.

Male caregiver statistics

Women provide the majority of care to seniors in the U.S. In fact, fewer than 24% of unpaid caregivers are men. That percentage is far higher than it used to be, as only 11% of family caregivers in 1995 were men. While statistics aren’t available for earlier years, it’s safe to assume that the percentage of male caregivers is trending upward as gender roles in society become more aligned.

Society tends to view women as more naturally nurturing than men. Until recent decades, men were more likely to work outside the home, making them less able to provide continuous care.

For sandwich generation caregivers, childcare and eldercare are often performed by the same parent. Because women also spend overwhelmingly more time on childcare, the responsibility of family caregiving may fall to them as well.

Military-connected status of caregivers

Caregiving may be more prevalent in military-connected families than in their civilian counterparts, according to the Blue Star Families’ (BSF) Caregiving in Military Families: 2020 Military Family Lifestyle Survey Special Report.

- 5.5 million people in the U.S. are military caregivers.

- 28% of those caregivers in military families are providing care for a parent or grandparent, while 35% are caring for a child with special needs.

- With a mean caregiver age of 37 years old, military family caregivers are younger than caregivers in the overall U.S. population.

The demographics of military caregivers differ from their civilian counterparts in the following notable ways:

Expanded concept of “family.” Within the military subculture, the concept of family may include non-relatives in the military community, such as battle buddies, fellow unit members, fellow military spouses, and military children. As such, 15% of military-family caregivers provide care to a non-relative who is the spouse or child of another active-duty service member.

Invisible wounds. These military-connected caregivers are more likely than their non-military-connected peers to be caring for people with mental, emotional, and physical health issues.

Lack of health coverage. Almost one in three post-9/11 military caregivers do not have health care coverage or VA benefits. This lack of health coverage is twice that of civilian and pre-9/11 military caregivers, as noted by the RAND Corporation.

Caregiving statistics by race

The majority of unpaid family caregivers in the U.S identify as non-Hispanic and white. However, a higher percentage of Asian American and Black U.S. residents provide family care than white residents do. While 75% of the U.S. population is white, 61% of caregivers are. Though only 13% of the U.S. population is African American, 14% of caregivers are.

- 61% of caregivers of someone age 50+ report being non-Hispanic white.

- 17% identify as Hispanic.

- 14% identify as African American or Black.

- 5% identify as Asian American or Pacific Islander.

- 3% identify as another race or ethnicity or multiracial.

African American and Black caregivers: A closer look

- African American caregivers are, on average, younger than their counterparts, at 47.7 years old.

- They are more often unmarried.

- African American caregivers report lower household incomes than non-Hispanic white and Asian caregivers.

- African American caregivers are more likely to be responsible for high-intensity care, providing 31.2 hours of care each week and assisting with multiple ADLs and IADLs as well as medical care.

- Most African American caregivers also work a weekly average of 37.5 hours and are most likely to report a negative financial impact from caregiving.

Asian American and Pacific Islander caregivers: A closer look

- Asian American caregivers are, on average, 49.3 years old.

- They are more likely to live with a spouse or partner and reside in a multigenerational household.

- Asian American caregivers report the highest education levels and household incomes of all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

- They typically work for an average of 36.7 hours a week while providing care, and while they report taking more time off to support loved ones, they’re often in more salaried jobs and report fewer negative career impacts.

Hispanic caregivers: A closer look

- At only 43.3 years of age, Hispanic caregivers are, on average, younger than any other U.S. demographic.

- They generally live with a spouse or partner and are the most likely to also be caring for a child under the age of 18.

- Hispanic caregivers typically work an average of 36.7 hours a week at an hourly-pay, non-salaried job, and they’re also likely to report a negative financial impact from caregiving.

Responsibilities of family caregivers and their impact on health and daily life

Caregiving is a difficult job that requires extensive time and energy. Family caregivers can be affected by their duties for years to come.

Caregiver duties and specialties

Every family has different care needs based on a senior’s medical status, ability to perform activities of daily living, and cognitive capacity.

- 99% of caregivers help with at least one IADL, like cooking, cleaning, laundry, or medication management.

- 60% help with at least one ADL, such as dressing, bathing, or using the toilet.

- Over 90% help with transportation to and from appointments or activities.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s caregiver statistics

Less than half of family caregivers — about 16 million — assist a person with dementia. They often have more demanding caregiving duties on top of the assistance mentioned above. They’re more likely to provide “high-intensity care,” according to the level-of-care index providers use to determine the amount of time spent caregiving. Dementia caregiver statistics vary from those of non-Alzheimer’s caregivers.

- Dementia caregivers also report higher amounts of strain, mental and physical health problems, and caregiver burnout, according to a study of 1,500 family caregivers in The Gerontologist.

- Over half of dementia caregivers provide care for four years or more, significantly longer than family caregivers for people with other age-related diseases.

- People with dementia typically require more supervision and are less likely to express gratitude for the help they receive (due to inability). As a result, caregivers are more likely to be depressed.

- Dementia caregiving increases mortality risks, even for healthy caregivers. Despite a significantly lower risk of mortality at the start of care, 18% of healthy spouse caregivers die before their partner with dementia, according to data culled from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Health and Retirement Study.

Long-term health effects of caregiving

Caregiving can be a rewarding role that helps form bonds between generations. However, it may significantly affect the physical and mental health and well-being of caregivers over time through caregiver burnout.

- Unpaid family caregiving for 20 hours or more a week results in impaired self-care, increased depression and psychological distress, and worse self-reported health, according to 2018 research conducted by Maastricht University.

- Caregiver depression increases as the elderly relative’s level of function declines. An estimated 30-40% of dementia caregivers and others providing high-intensity care experience depression.

- Only four in 10 caregivers would rate their health as “excellent or very good,” according to AARP’s 2020 Caregiving in the U.S. survey.

- 53% of caregivers have been diagnosed with two or more chronic conditions. That’s 14% higher than the general U.S. adult population, according to the CDC.

- Nearly half of caregivers are concerned about the physical strain that comes with caregiving, according to a survey from SCAN Health.

- 44% are concerned about the emotional strains of caregiving, according to the SCAN Health survey.

Financial impact of family caregiving

On average, family caregivers spend $7,242 annually, or 26 percent of their income, on providing care to a senior loved one. 22% of caregivers report using all their short-term savings, while 12% percent say they went through all their long-term savings while taking care of elderly parents at home, according to an AARP report.

Caregivers who are retired or no longer working may go through their savings even more quickly, leaving themselves with little money for care as their health needs increase over time.

Caregivers may incur extra expenses like:

- Higher utility bills

- Extra groceries

- Medical needs, such as prescription medication and bandages

- Accessibility devices, including hearing aids, wheelchairs, and walkers

- Incontinence supplies

- Transportation-related costs

- Clothing and personal care needs

- Home modifications